Vulnerability Remediation: Down and Up We Go

If you’ve ever opened a vulnerability report, sighed, and thought,

“Okay… but how did this thing even get here?”

this post is for you.

Modern security tools are actually very good at finding vulnerabilities.

In fact, they’re so good that they’ve created a new kind of pain: the effort required to figure out how to fix what they found. And most security tooling often stops at detection.

The reason remediation always feels behind isn’t because engineers are careless, slow, or bad at security.

It’s because detection goes down the stack, and remediation has to come back up.

And that round trip is where all the time goes.

How Vulnerability Detection Really Works (AKA: Going Down)

To do a good job, modern scanners don’t just glance at your application and call it a day. They aggressively decompose whatever you give them.

A typical scan looks like this:

- Start with a container image or VM

- Crack it open into OS packages (apt / yum / apk)

- Inspect system libraries

- Inspect runtimes (JRE, Node, Python, .NET)

- Walk language package managers (npm, pip, Maven, etc.)

- Traverse transitive dependencies

- Match CVEs to exact versions at the deepest possible level

This is the right approach.

Without this level of decomposition:

- Deeply nested vulnerabilities are missed

- Results become vague and low confidence

- CVEs can’t be reliably matched to what’s actually running

So far, so good.

Detection must go down.

Remediation: Where Everything Starts to Hurt

Here’s the catch:

The place where a vulnerability is detected is almost never the place where it can be fixed.

Scanners typically report findings like:

- “CVE-XXXX-YYYY in

libfooversion 1.2.3” - “Vulnerable package found in layer N of image Z”

Accurate. Precise. Technically correct.

Now comes the part that lands on an engineer’s plate:

“Alright… which knob do I actually turn to make this go away?”

That’s where remediation stops being mechanical and starts being detective work.

Because remediation requires going back up the stack.

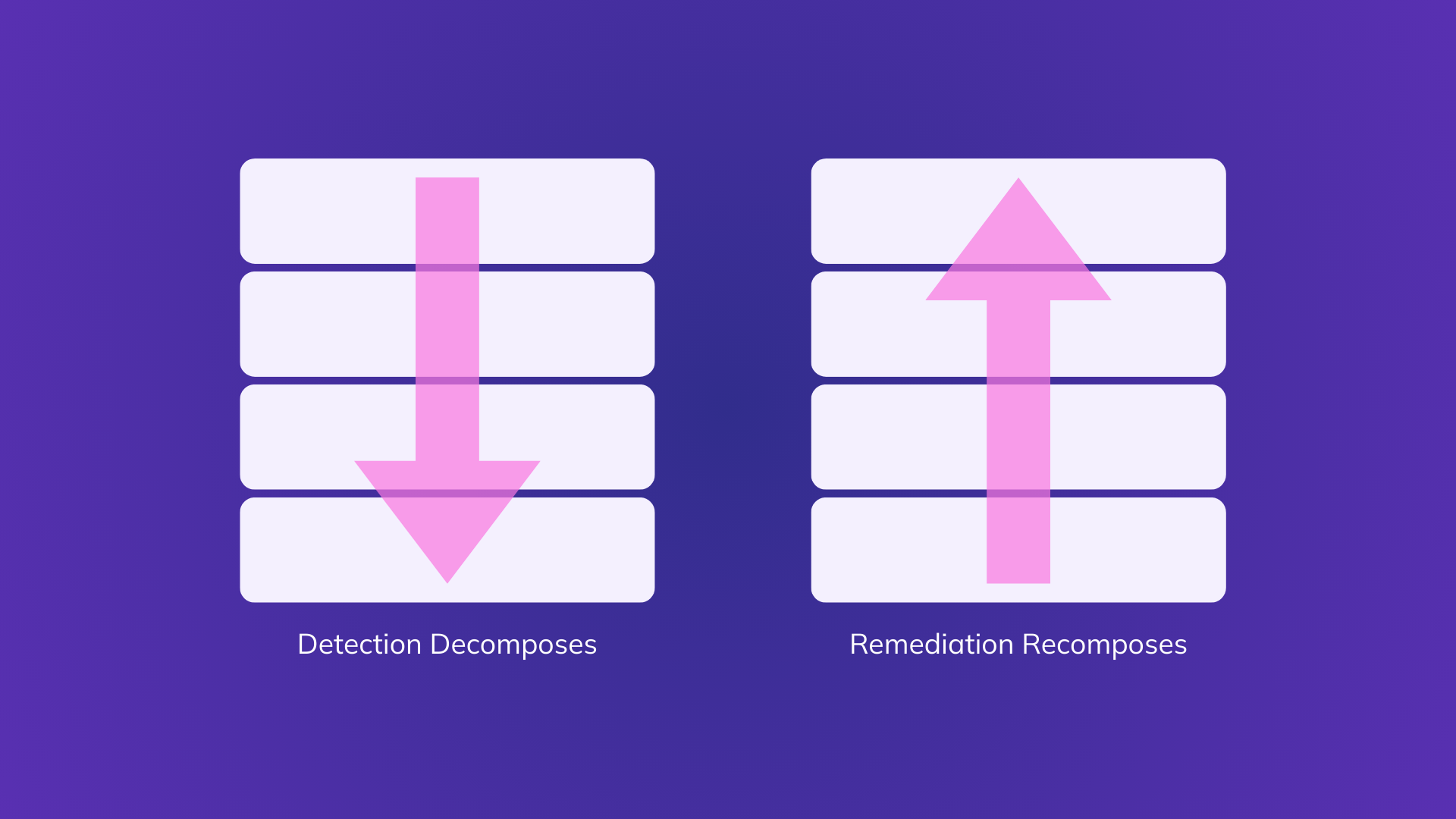

Detection Goes Down. Remediation Goes Up.

Here’s the mental model that explains most remediation pain:

- Detection decomposes software

- Remediation requires recomposing it

You’re handed a leaf node in a dependency tree and asked to:

- Figure out how it got there

- Decide whether it matters

- Identify who owns the layer that can change it

- Make a change that doesn’t break production

Security tools walk down the stack to find the truth.

Engineers must climb back up the stack to make change.

That up-and-down journey is the work no scanner shows you.

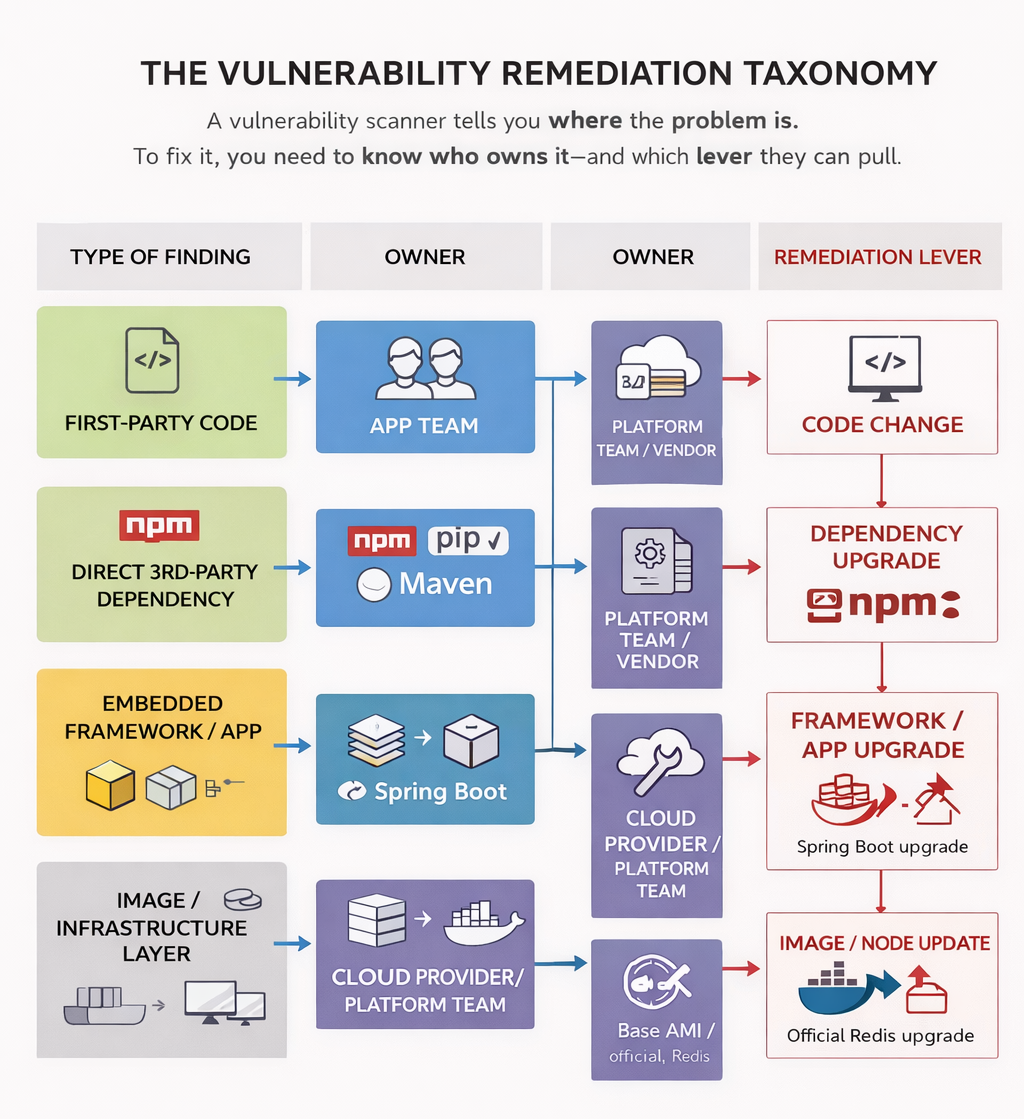

The Four Kinds of Remediation (Where Fixes Actually Live)

In practice, almost every vulnerability falls into one of these buckets. Let’s walk through them the way engineers actually experience them.

1. First-Party Application Code

“Yep, this one’s on us.”

What The Scanner Tells You

A vulnerability mapped directly to your code:

- A file

- A function

- A compiled artifact

Think SQL injection, deserialization bugs, authz mistakes.

This is the cleanest case.

Why it’s Still Not “Easy”

Even here, the scanner quietly assumes:

- The code path is reachable

- The issue is exploitable

- You can safely change it today

Reality is messier.

A Very Real Example

Context: Java service

Finding: SQL injection in a repository method

Scanner: “Critical vulnerability in UserRepository.java”

Reality: The method is only reachable via an admin-only endpoint behind multiple checks.

The Actual Fix:

- Verify reachability and exploitability

- Refactor query

- Add tests

- Redeploy

Where Teams Fall Behind

Perfect signal doesn’t eliminate engineering time, review, CI, or deployment risk.

2. Direct Third-Party Dependencies

“We don’t own it, but we did choose it.”

What The Scanner Tells You

A CVE in a package or binary you include directly:

- npm / pip / Maven dependency

- Vendored CLI or tool

- Something baked into your image

Usually with a suggestion like:

“Upgrade package X”

Why This Slows Everything Down

Because “upgrade X” is rarely the full story.

You immediately need to answer:

- Is this runtime or build-time?

- How was it installed?

- What else depends on it?

- Will a minor bump break anything?

A Painfully Familiar Example

Context: Container image includes awscli

Finding: CVE in urllib3

Scanner: “Vulnerable urllib3 detected”

Reality: urllib3 is bundled transitively by awscli.

The Actual Fix:

- Upgrade

awscli - Or move it to a builder image

- Or change how it’s installed entirely

Where Teams Fall Behind

The scanner points at the leaf.The engineer has to find the branch.

3. Indirect Dependencies via Platforms and Embedded Third-Party Software

“This isn’t my code, and it isn’t a library I can upgrade.”

This category is often described as “framework dependencies”, but that framing is too narrow.

In reality, this bucket includes entire third-party applications and binaries that embed their own dependency trees and are effectively black boxes to you.

What The Scanner Tells You

A CVE in a deeply nested dependency, for example:

- A Java JAR buried inside a vendor application

- A Go library embedded in a statically linked binary

- A component pulled in via a platform-managed distribution

The scanner reports the vulnerable component, not the thing you can actually change.

Why This is Fundamentally Different From Normal Dependencies

Because you cannot:

- Upgrade the dependency directly

- Patch the binary

- Rebuild the artifact with a fixed version

The only entity that can fix it is the vendor that shipped the software.

Through An Example Lens

Example 1: Embedded System Agents

Context: Linux host or container

Finding: CVE in a Go networking library

Scanner: Vulnerability detected in Go module golang.org/x/net

Reality: The vulnerable library is embedded inside aws-ssm-agent.

You are not going to:

- Recompile the agent

- Swap out the Go module

- Patch the binary in place

The Actual Remediation:

- Check whether the vendor has released an updated package

- Upgrade

aws-ssm-agentvia the OS package manager - Or wait for the platform to ship an updated version

The real fix is:

Upgrade the third-party application, not the dependency.

Example 2: Vendor Applications with Bundled Libraries

Context: Data platform deployment

Finding:

/usr/local/pentaho/9.2/data-integration/lib/ jackson-databind-2.9.10.2.jar

Scanner: CVE in com.fasterxml.jackson.core:jackson-databind@2.9.10.2

Reality: That JAR is bundled inside Pentaho.

You cannot:

- Replace the JAR safely

- Override the classpath without risking breakage

- Treat this like a normal Maven dependency

The Actual Remediation:

- Check Pentaho advisories

- Determine whether the CVE applies to their usage

- Upgrade Pentaho to a fixed release

Again:

The scanner flags a library.

The fix lives at the application level.

Where Teams Fall Behind

- Security tools point at what is vulnerable

- Engineers must identify who owns the fix

- Ownership often sits with a vendor or platform team

- The remediation path may not even exist yet

This is where findings age the longest. Not because teams ignore them, but because control has shifted upstream.

4. Immutable images, base images, and managed runtime artifacts

“Yes, it’s vulnerable. No, I can’t fix it in place.”

This category is broader than “base images” and more constraining than it sounds.

It includes anything delivered as a sealed artifact:

- OS base images

- Vendor container images

- Managed runtime images

- Platform-provided VM or node images

What The Scanner Tells You

CVEs in OS or bundled software:

glibcopenssl- Redis, NGINX, PostgreSQL binaries

- System libraries inside container images

The report is usually precise. But completely unactionable at the leaf level.

Through An Example Lens

Example 1: Managed infrastructure

Context: Managed Kubernetes cluster

Finding: CVE in glibc

Scanner: Critical OS vulnerability detected

Reality:

- Nodes are immutable

- OS is provider-managed

- Patching is done via new images

The Actual Remediation:

- Verify the provider has released a patched image

- Upgrade the node group

- Roll nodes and drain workloads

No patching. No SSH. No hotfix.

Only rotation.

Example 2: Vendor container images

Context: Running the official Redis container image

Finding: CVE in Redis or linked system library

Scanner:

Vulnerability detected in Redis image layer

Reality:

- You are running a vanilla vendor image

- You do not patch Redis inside the container

- You do not modify system libraries inside the image

The Actual Remediation:

- Pull a newer Redis image

- Redeploy workloads

- Validate compatibility

The only viable lever is: Upgrade the image.

Where Teams Fall Behind

- Images are immutable by design

- Fixes require rebuilds or rotations

- Rollouts carry operational risk

- Decisions were often made months earlier

From a security standpoint, these findings are “known”.

From a remediation standpoint, they’re gated by infrastructure lifecycle.

Why Categories 3 and 4 Matter Most

Categories 3 and 4 are where vulnerability backlogs accumulate. Not because teams are slow, but because:

- The scanner reports components

- Engineers control artifacts

- Vendors control dependencies

- Providers control timelines

The farther down the stack detection goes, the less local the fix becomes.

And that is the core structural reason remediation always feels behind.

The Real Reason Remediation Always Feels Behind

Security tools are doing exactly what they should do.

They go down the stack to find real issues.

Engineers, meanwhile, are forced to go up the stack to fix them:

- Across abstraction layers

- Across ownership boundaries

- Across tooling and teams

That recomposition work is invisible in most vulnerability reports.

Closing that gap requires security tooling to move beyond reporting vulnerable components and toward reasoning about where fixes actually live and how they can be applied safely in real systems.

Final Takeaway

If vulnerability remediation feels slow, it’s not because engineers don’t care.

It’s because:

Detection decomposes software.

Remediation requires recomposing it.

Until security tooling becomes better at surfacing where the fix actually lives, not just where the vulnerability was found, teams will keep looking behind, even while doing everything right.

Down we go to find the bug.

Up we go to actually fix it.

Featured Blog Posts

Explore our latest blog posts on cybersecurity vulnerabilities.

Ready to Reduce Cloud Security Noise and Act Faster?

Discover the power of Averlon’s AI-driven insights. Identify and prioritize real threats faster and drive a swift, targeted response to regain control of your cloud. Shrink the time to resolution for critical risk by up to 90%.